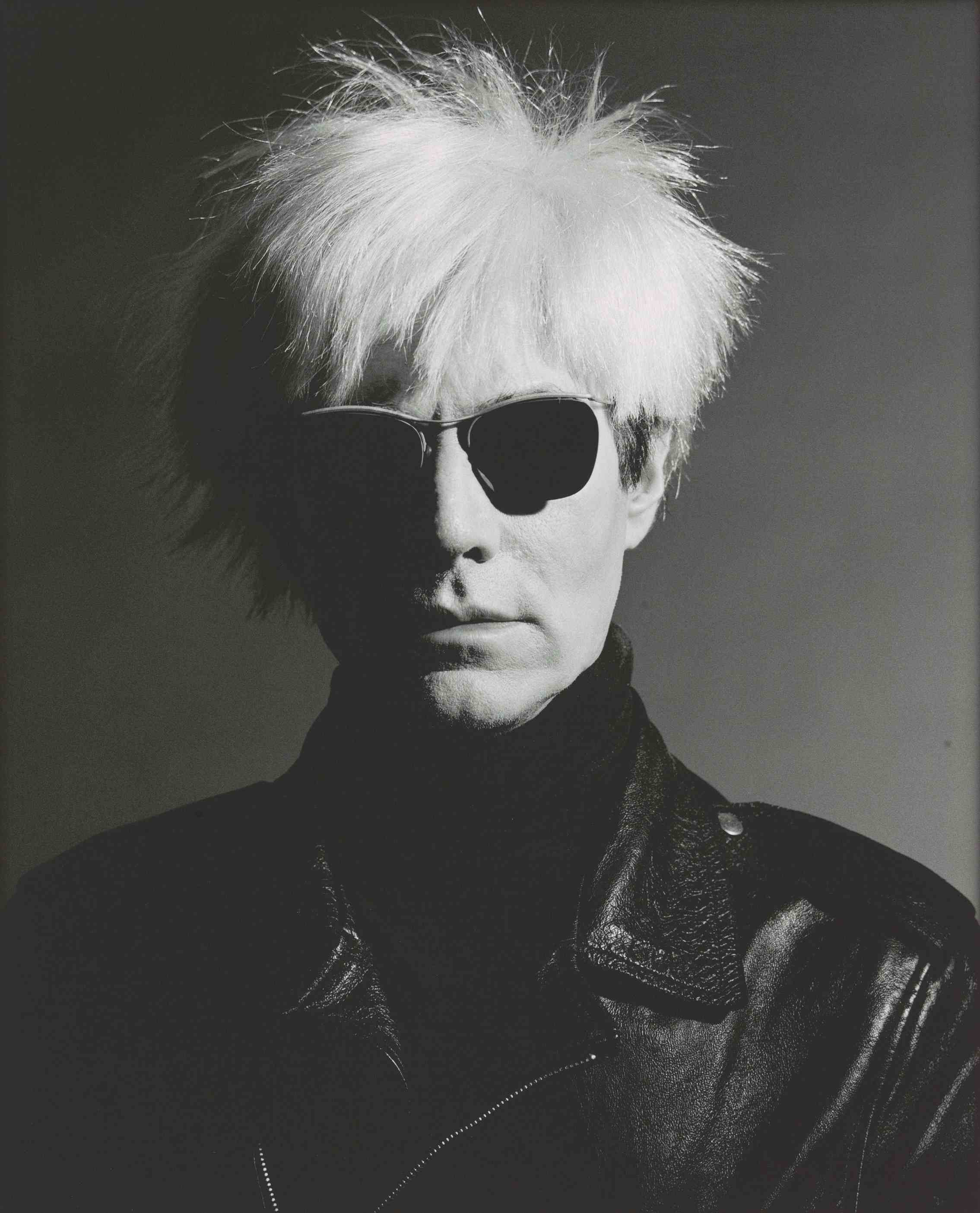

“It’s as though Western Art began with Andy Warhol.” – Robert Hughes, The New Shock of the New, 2004

In his 2004 documentary, commenting on the sudden change in contemporary art between 1955 and 1965, Robert Hughes declares a clean break from previous styles of art with the above statement.

So, how can he make such a bold announcement? How does Andy Warhol act as a fulcrum for contemporary art? What changed?

The short answer: everything.

Jose Ortega y Gasset writes that man is man, plus his circumstances. If we are to understand Warhol, therefore, we must also understand his circumstances. Andy Warhol’s were post-war America, the boom years, the Atom Bomb years, the birth of the jet-age, the space age and the birth of a culture in rapid transition. Between 1950 and 1970 the number of people living on farms in the United States dropped by over 20 million people, at a time when the population of the nation was only about 170 million. The nation was moving from an agrarian society to an industrial, and soon, post-industrial culture. In 1950 popular music was played on acoustic instruments, by 1960 popular music was electronic.

On May 02, 1952 the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) launched the jet age by offering the first commercial jet flight in history, transporting 36 passengers from London to Johannesburg in a four-engined de Havilland Comet.

Media changed.

Television became ubiquitous.

The number of television programs skyrocketed, as did the amount of advertising to which American audiences were exposed. In 1950, the average American was exposed to approximately 3000 ads in their lifetime. Since then that number has grown by orders of magnitude and today the average American is exposed to 3000 ads by lunchtime. This was the golden age of American advertising, the Madison Avenue years – and and as a successful advertising illustrator, this was Andy Warhol’s world.

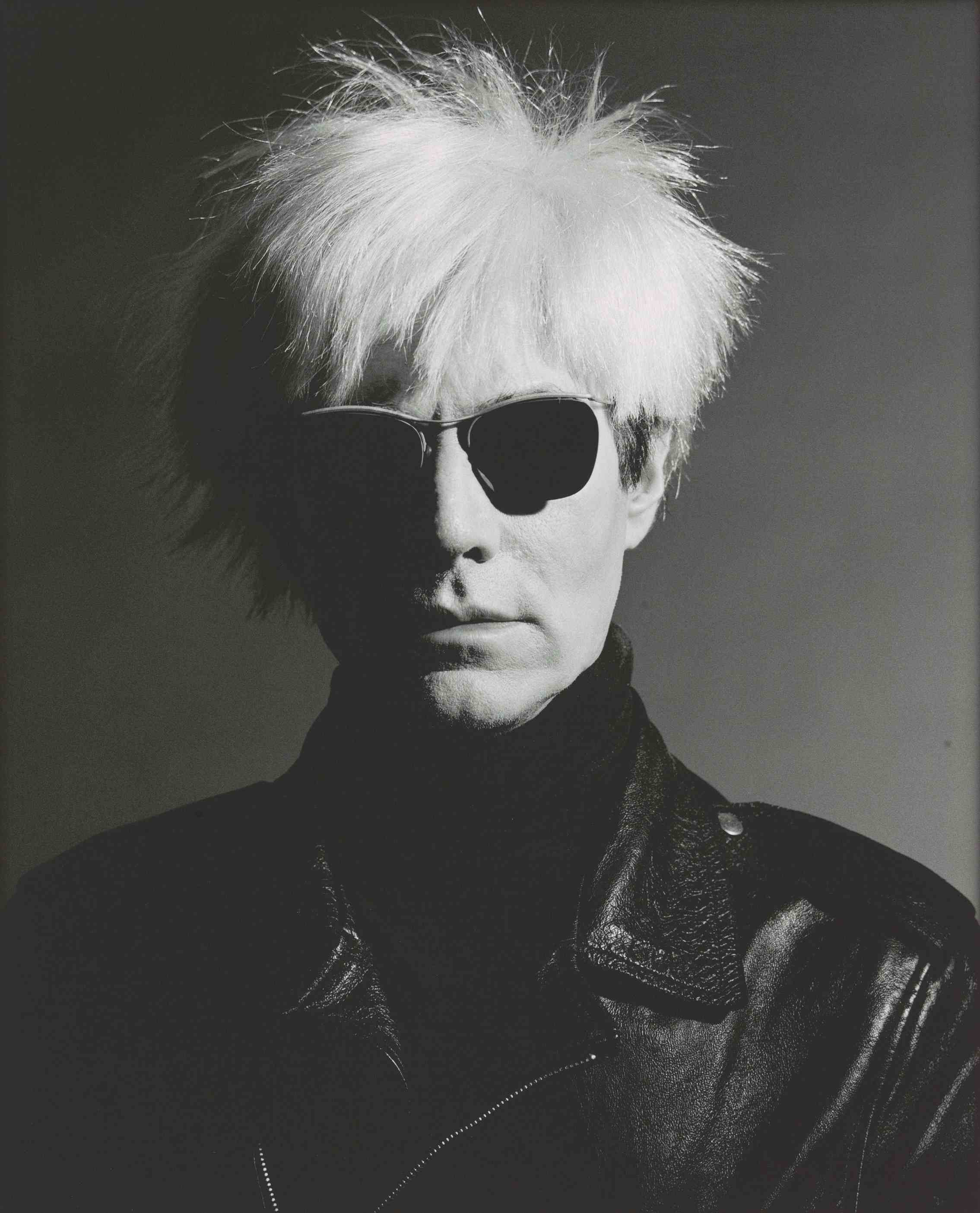

In his 1951 book, “The Mechanical Bride”, Herbert Marshall McLuhan writes about newspapers, the undisputed king of all media at the time. “Ours is the first age in which many thousands of the best-trained individual minds have made it a full-time business to get inside the collective public mind,” writes McLuhan, concerned about the very early stages of the media explosion of the 1950’s and 1960’s. But 1951 was only the beginning of the explosion. To borrow a metaphor from the period, the mushroom cloud of the media explosion was yet to come. The medium was not quite yet the massage.

In the 1950’s, Warhol was one of those individuals McLuhan describes in his preface to “The Mechanical Bride” – one of the thousands of well trained minds making it their business to get inside the “collective public mind.” His simple drawings belied the fact that they were often traced from photographs. Nobody knew that Warhol, even then, was repurposing images for public consumption.

Andy Warhol wrote “once you ‘got’ Pop”, you could never see a sign again the same way again. And once you “thought Pop”, you could never see America the same way again.”

Pop Art was born out of the invention of Pop Culture. Today we assume that the term “popular culture” has always been around, when, in fact, the term was first used at the dawn of the 1960’s. Andy Warhol exhibited his first paintings, images taken from comics and advertising, in 1961.

Guy Debord publishes “The Society of the Spectacle” in 1964. Tom Wolfe publishes “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby”, (in which the term “Pop Culture” is used and discussed as a new phenomenon) in 1965. From 1960 to 1967, when color television became standard, the landscape of Western culture was changed forever with a tsunami of electronic media. The “Spectacle” was the representation of all of the products produced for consumption, from durable goods to entertainment, and it was not long before the images themselves became products for consumption. Andy Warhol’s “Campbell Soup Can” first appeared in Los Angeles, at Irving Blum’s Ferus Gallery in 1962 – the ultimate expression of a consumer society focused in on itself, defining itself through the products it manufactured.

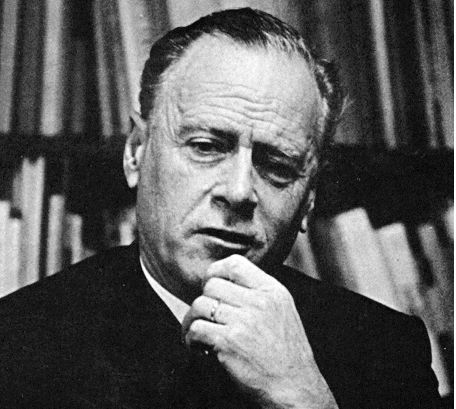

In 1969, seventeen years after the first commercial jet flight, this same society put a man on the moon, and televised the event for the world to consume. The moon landing was as much a media event as it was a historical achievement. Our collective memory of the moon landing is entirely based on a collection of electronic images.

It is a vicarious experience. As such, it produced an explosion of imagery and sounds; all faithfully reproduced in myriad variety by electronic and mechanical means. This is how we experienced the Kennedy assassinations, the Vietnam War, the Paris riots of 1968 – these were first and foremost spectacles. The population of the time could only experience the events throughout their electronic reproduction. Today, we remember freeze frames, grainy newspaper photos, slow motion film – these are the representations of the events, the signifier not the thing signified. Signs. Posters. Silk-screened t-shirts.

So now let’s take a look at art in this milieu. The moderns had already stripped art of narrative and subject. The abstract expressionists had eliminated form and replaced it with gesture or color. Ad Reinhardt paints a black canvas in 1963. Okay, so now what?

Painting itself was struggling for relevance. But not the image. The image was alive and well and available for mass consumption. And mass consumption was what it was all about.

The Western world, Debord’s Society of the Spectacle, was in transition; in fact, transition would characterize the decades from 1950 to 1980. In 1950 industry was concerned with manufacturing the best products they could. A Louis Vuitton handbag was a plain brown leather handbag, but exquisitely constructed of the finest materials. A Cadillac was the ultimate expression of the automobile. By the 1970’s the concern was no longer to manufacture the best, but to manufacture the most. Industry changed. Consumption changed and art changed along with it.

In 1976, Tom Wolfe, the literary version of Andy Warhol, publishes his essay “The Me Generation” in New york magazine. Here, the generation that coined the term “Pop Culture” turns 30. Wolfe describes the character of this generation as the first to not have a sense of belonging to the greater concept of a nation, but a generation of individuals completely out for themselves. This was the beginning of an American culture obsessed with itself and with celebrity and status. Celebrity for the sake of celebrity. Andy Warhol once said that he liked photographs as long as they were in focus and of somebody famous. This was a culture where the image was the end product.

It was right here, at this moment in time, that the Mona Lisa ceased to be a painting.

Ask yourself, how many people on earth know the image of the Mona Lisa? It seems safe to say that, at this point in time, almost everybody on the planet earth has seen an image of the Mona Lisa. Now ask yourself, how many of those people have seen the painting in person? Almost none, by comparison. Leonardo’s masterwork is ubiquitous. On coffee mugs and beach towels and sneakers. Dinner plates, comic books. But as an image of a painting, not a painting. Very few people experience the Mona Lisa as a painting. Just like the moon landing and Che Guevara, she is now a t-shirt.

The signifier not the thing signified.

Andy Warhol understood this innately.

So, returning to the original question of this essay, how is Warhol the fulcrum for contemporary art? Because after Warhol there are no more “isms”.

The book “Individuals: Post Movement Art in America” captures the concerns of this period. Here is an art world with no more International Style, no “ism” to define it. Before Warhol art had a thesis – the definition of what was art. After Warhol there is no thesis, art is anything, can be anything. Conceptual Art emerges, along with performance art, painting is reduced to regionalisms and art in general seems focused on the “expression of personal neuroses”, to return to Mr. Hughes for a moment.

Curiously, It was a scene from the late Robert Hughes’ 2009 documentary The Mona Lisa Curse that prompted this essay. In the documentary Mr. Hughes visits the home of Alberto Mugrabi for the apparent sole purpose of denigrating Andy Warhol in front of one of his most well known collectors. “I thought he was one of the stupidest people I’ve ever met in my life” he tells Mr. Mugrabi. Well, besides annoying Mr. Mugrabi, the statement is actually pointless. Let’s face it, Jackson Pollock was no great intellect. Intellectual prowess has not been required of fine artists for decades. In fact, the foremost champion of the Abstract Expressionists, Clement Greenberg stated flatly that most visual artists do not have the capacity to discuss their works in a historical or theoretical context – a statement prompting me to throw the book against the wall, even as I had to acknowledge that he was probably right.

So… returning to Robert Hughes; he went on to say that he “did not believe that Warhol contributed much to the art of painting.”

With all due respect to the late Mr. Hughes, what made him think that Warhol intended to make a contribution to painting in the first place?

Warhol was first and foremost a media artist.

“I’m for mechanical art” he writes, “When I took up silk screening, it was to more fully exploit the preconceived image through the commercial techniques of multiple reproduction.” That’s it. I apologize, Mr. Hughes, but it was never about painting. It was about Coca-Cola and color television. It was about media.

Because Andy Warhol understood something then that has become an integral part of our society today – that everything, absolutely everything that is manufactured, examined, contemplated, discussed, looked at, purchased, discarded, bandied about and otherwise exploited, is MEDIA.

At a recent review of PhD candidates at the University of California at Santa Barbara Media Arts TransLab, one of the professors from the Syracuse University Architecture department and I spent the day discussing the concept of architecture as media. So that’s it, baby. The Society of the Spectacle, once viewed at a distance by consumers, has closed the gap. It has absorbed us completely. Our clothing is covered with corporate logos, investment bankers can have visible tattoos now and behaving like a rock star is the right and privilege of every Western youth, no longer the purview of just a few ill behaved megalomaniacs.

Andy Warhol wrote,

“What’s great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you can know that the President drinks Coke. Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too.”

Well, now everybody on the planet earth can download computer programs that will turn your family snapshots of little Timmy, or your aunt’s dog into multiple Andy Warhol images, just like Elizabeth Taylor, Brando and Elvis. As Andy himself might have said … Nifty!

Andy Warhol once wrote that he wanted to be a machine.

Warhol did more than become a machine.

He never lived to see it, but Andy Warhol became an algorithm.